I love that he had a work shirt already prepared in the vehicle, which he put over his regular shirt before we hiked in. I was not prepared for this given how easily Mr. Bak had strode into a bamboo grove with a clear path. If Mr. Jo hadn't been leading me into the brush, I wouldn't have even thought there was a way in. He had to saw away several fallen bamboo stems in our "path" and I wondered how in the world we were even going to get OUT of this place carrying bamboo. We climbed for a while through what seemed to be no route at all but he knew exactly where he was going. If you ask me to distinguish one bamboo from another, I wouldn't know, but he said, What's good to the eye is good. So he picked a plant and got to work.

We wanted one that was about three years old with a lot of length between nodes, since we were going to have cut them out (unlike the way he usually works). To him, it's a waste, since he's so used to working with nodes and having nice long splints. But nodes in a hanji screen would make sheet formation really hard and the sheets would end up being uneven. It is remarkable to me how easy it is to cut down bamboo, and that you don't hack at it and then let it fall down with a giant "TIMBER!" call. They are too close to each other to fall down like that, and tall, so you saw on both sides and then just pick it up and stand it next to its stump.

Then you have to figure out how to get it horizontal. There's a lot of sawing to help parts of it come down. And in this case, we didn't need to keep the length of the plant intact, so Mr. Jo chose this length for us to bundle and carry down. I had only brought my tiny backpack so I could only shove one piece into it to bring home as a sample of an intact bit, a piece he had cut off and thrown away after I asked to practice sawing.

This is the first time I asked him to take pictures of me because otherwise how would you believe that I was there? He was very kind about doing this whenever I asked, which was as little as possible because it feels embarrassing.

Mr. Jo is like a kindred spirit because he keeps very neat and his car is spotless, so he has ways of dealing with loading dusty bamboo into the car, putting his work shirt onto the center console in the back seat that he opened to fit the pieces we brought down. I managed with only a slightly sprained ankle and scraped knee on the way down.

This time, instead of the "clean" weaving studio near the second city hall building downtown, we went to his "dusty" studio very close to his home. A couple used to rent the back of the building but when they moved out, he took over all the rest of the rooms and that's where a ton of his work is stored. So it's really just one concrete lower studio and then the rest of the place is pretty clean as he is fastidious.

I can't find this in my notes but I'm pretty sure a friend of his made this and it says Tongyeong yeomjang (screen maker) but someone who knows Chinese characters can correct me.

This was our work space for the next two days, and also on my last day because I needed more practice and wanted to shoot his knives. At this point, his neighbor Bak Kyoung-hee came by to say hi as she's not always in town, and we had a nice long talk that gave me some hope because there are people out there who understand the issues of preserving and continuing traditional heritage, but in a way that artists and practitioners can make a living as well.

By the time we got to work, I think we were both worried about how much time we lost to chatting, lunch, and tea upstairs with Mrs. Bak. First we had to shave down the nodes to minimize their bulk. I say we but he did most of this because I was not good at using a giant knife for this particular job.

Bamboo has a very thin outer layer that needs to be scraped away. You want to remove the green but not more, as the outer grain is the strongest and what we're looking to isolate. Also, it's much easier to work with fresh bamboo so that's why we worked this way, to process immediately after harvest.

The ends we weren't using were cut away, though it seemed a little bit of a waste. I did grab one little stumpy piece as well to be able to show a shorn node.

We had six lengths in total to work with but I was so slow that we did not get through a whole lot of this when I was in the studio. All cuts are parallel to the grain, so from the top to the bottom of the plant. First you split in half. Then quarters, eighths, 16ths.

This is all done by hand with a large bamboo knife with a thick back to aid in the splitting.

The skill of course is to make very even cuts so that the pieces aren't wider on one end than another, and that every time you split, you halve the piece in your hand (rather than wavering over to splitting it into 1/3 and 2/3rds, or worse. I wish I could explain this better in words/English but my head is not capable right now).

Somewhere around 16ths and 32nds, you have to pause and remove the inner flesh of the bamboo, which is weaker and burned as trash (or used as disposable chopsticks, I'm guessing). The key here is not to remove it ALL in the first round, because you can take too much away or damage what you want to preserve of the outer grain.

This is also tricky, the second removal of inner flesh. Because again you don't want to take away too much. I was not good at controlling the removal at the end, and my pieces would always end up thicker at the top and way too thin at the bottom. This is 100% knife and arm skill: how you hold the piece against your body, and how you guide the knife in case you are taking too much or too little flesh away, and I kept going in the wrong direction.

This is also tricky, the second removal of inner flesh. Because again you don't want to take away too much. I was not good at controlling the removal at the end, and my pieces would always end up thicker at the top and way too thin at the bottom. This is 100% knife and arm skill: how you hold the piece against your body, and how you guide the knife in case you are taking too much or too little flesh away, and I kept going in the wrong direction.

Even though this requires electricity, I endorse this method!

This was a different batch that we processed, bamboo that had sat around for a while (see how the color shifts from the green quickly to this tan/brown color) in his studio. You can see the points at the end. When working with bamboo that has sat around for a while, you need to get it in water so it's easier to work with.

Now you need to prepare your drawplate. Mr. Jo works a little differently from the other two screen makers. Instead of using extremely rigid steel, he gets softer/thinner stuff that he finds wherever. These four nails are his tools in making the holes. He said that he's always scanning from metal that would be good for this purpose, which explains the bit at bottom right, part of a steamer basket!

You have to take a series of nails that go from dull to sharp to shape the hole and make the right size. It needs to protrude out just so and then you file it, as it's essentially shaving each splint. It's not just a flat hole flush to the surface.

I asked if this was the lid of a rice bowl and he said, it looks like it might be, huh? It certainly does, hammered flat and used for tons of splints.

So much of a working person's tools and studio and waste is like treasure for an artist.

The way that Mr. Jo gets around using such thin and flexible steel for his drawplates is by using a wrench to support it so that it doesn't deform as you pull splints! Brilliant. These are in a vise.

This is the step that transforms these splints that look like a square in cross section into ones that look like a circle in cross section. You have to draw every splint through a drawplate with holes that get smaller and smaller at least two times for regular blinds, probably 3 or 4 times for hanji screens depending on how thin you are able to cut your splints in previous steps.

You can see the shavings coming off of the splint and my weird left hand position that is evading the splint for fear of splinters. You put the point of the splint into the hole on the other side of you, and then pull on the end with pliers and pull through.

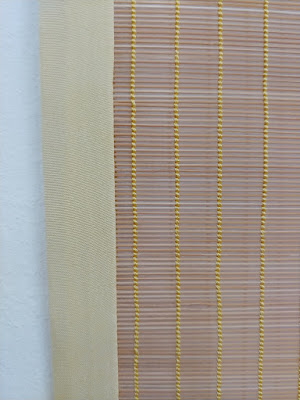

On Day 5 (of eight), Mr. Jo had to go to church. I had hoped to have the morning off to sightsee but he insisted I go back to the dry studio and start weaving on my own until he arrived at 2pm. I managed to finish the first half of the screen but had to wait for him to get the edgesticks on. We used two instead of one only because he didn't have wide enough bamboo. Here I'm holding the ends of the fishing line after tying off each one before trimming.

Mr. Jo is inspecting an actual hanji screen to figure out how we're going to set up the lines for the second half of the screen, which have to fall in between the current chain lines on the first half.

If you don't know what to look for you might not see it, but there is ONE line set up closer to the right side of this picture. Instead of taking a needle to thread the line we just used the line itself to get set up on two splints before winding onto a warp weight.

We had only wound the warp weights on one side so that the other half's end was free to thread onto the screen. I think we only got this far before it was time to head to the presentation by the other national treasure. Then we rushed off to dinner with church friends. Just the day before, Mr. Jo had been feeding me candy and I was telling him that I shouldn't eat it because I didn't want to go to the dentist. After we ate a giant meal of nothing particularly hard, I did a sweep of my mouth with my teeth and noticed a large chunk was missing from a back molar. I had probably eaten that piece of my tooth during dinner and called over to my teacher to tell him what happened. Miraculously, my tooth didn't hurt, but I was terrified about what might happen if we didn't deal with it. But after tea, he took us back to the studio to finish threading all of the rest of the lines and winding on warp weights. We worked past 9pm and the guest house owner was so worried that I wasn't home that she texted me!

The next day was Sunday, so we couldn't go to the dentist, and Mr. Jo works on Sundays like it's a weekday, so I didn't get a break either. He took me to the dry studio and told me to start weaving while he went to the other studio to process bamboo. He was back for lunch, and then went back to the studio in the afternoon, then back to pick me up to go home. You know what he was doing? Processing the rest of the bamboo that I was so bad at doing so that I'd have more splints to take home.

He said on Monday we'd go first thing to his dentist, whose wife had taken classes with him a few times and made three screens. He called in a favor to fit us in right before other people arrived, and the dentist was one of those loud proud men who quickly said that all my other teeth were a disaster. My teacher pushed him to get a crown made by the next day because I was leaving on Wed, and they gave me a discount on all the work because of Mr. Jo. I was shocked by how inexpensive a gold crown was, well under 50% of the cost of the same work back home. He stayed with me the whole time on both days and while I felt extremely vulnerable and exposed, I was touched by his insistence on staying and by his small gestures, like taking the slippers off of my feet while in the chair (here, you take off your street shoes at the entrance and swap them for slippers) or holding my face while I was in the chair recovering, asking how my other teeth were. He's only about 3 years younger than my dad and though our interaction could be awkward at times, I could tell he was very concerned.

More than one man has touched me here and aside from the one bad situation, it is clear immediately when the intention is one of care. In any student-teacher relationship, there are degrees of intimacy, and I was surprised by some of it as it felt so deeply feel like fatherly care—and I haven't been able to see my father for well over a year because of pandemic. I felt so fortunate to have met this teacher at this point. By the time that Yi Sunhee took these pictures of me (Mr. Jo was back at the bamboo studio working), I had seen the dentist and had something temporary on my tooth. The friends who have seen these pics already all said the same thing: "You look so happy!" All I felt was utter exhaustion, but it was affirming to have people who knew me recognize that I was finally deep in the stuff that holds so much meaning for me.

By Monday afternoon, I knew I had made decent progress but didn't think I was done given my previous estimate of weaving 2cm an hour. But just for kicks, I decided to measure the second half of the screen to check. It turns out I was spot on DONE! I called Mr. Jo and he said to add the edgesticks and tie off, then wait for him as he finished up in the bamboo studio.

After he inspected my work, we cut the warp weights off for the last time and started to measure off the sides to trim flush. Because the first half of the screen was where I started learning, it was all warped, but Mr. Jo did his best to measure straight.

It's always so satisfying to clean up the ends. I would have trimmed even more but this is one of many instances where you let the teacher do his thing. Maybe it would have been easier if I knew nothing, but in a way, now that I've been teaching for so long, I could feel his point of view better. As we neared the end, which felt like it happened all of sudden, he started to rummage around both studios to find things to give to me. I know this urge very well: when I have dedicated students or ones that I have gotten very fond of (they usually one and the same), I want to give them everything. I start to feel I haven't taught them enough, and so I give whatever I have left. It's part of preparing to say goodbye....for now.One of the details that would have been meaningless to me before I actually made a screen is this one (again, invisible if you don't know what you're looking for): Mr. Jo said that in the future when I weave, I need at every 25 splints or so combine two splints in one half twist to counteract the tendency for the screen to stretch at the ends. You'll see that twice in this picture.

He also showed me how to stretch the screen under weights when I get home to try and get the whole thing flat. Then he rolled it up tight and packed it with all of my splints in a few fastidious packages. We fought about him wanting to give me a bag to take it home in but I insisted that what I had would be fine. This was our penultimate day; I probably could have left after this but as I had a ride home two days later and also had major dental work scheduled, our last day was spent processing the remaining bamboo and learning briefly how to make patterns and work on a much larger screen while standing.

This was one of many wonderful scenes that opened up for me. When we were leaving, the woman who lived next door to the studio that houses other national treasures and intangible property holders insisted that she select some greens for Mr. Jo to take home. We walked into the side of her house and then up stairs that led to a tiny garden wedged between buildings. It was incredible to see what she was growing on that tiny patch of land that you would never even imagine was there from the street. She asked if I was his daughter, who is a year older than me and training in earnest to take on the family tradition. I'm not, but my father would have been glad to know that I was in good hands the entire time.

This was our work space for the next two days, and also on my last day because I needed more practice and wanted to shoot his knives. At this point, his neighbor Bak Kyoung-hee came by to say hi as she's not always in town, and we had a nice long talk that gave me some hope because there are people out there who understand the issues of preserving and continuing traditional heritage, but in a way that artists and practitioners can make a living as well.

By the time we got to work, I think we were both worried about how much time we lost to chatting, lunch, and tea upstairs with Mrs. Bak. First we had to shave down the nodes to minimize their bulk. I say we but he did most of this because I was not good at using a giant knife for this particular job.

Bamboo has a very thin outer layer that needs to be scraped away. You want to remove the green but not more, as the outer grain is the strongest and what we're looking to isolate. Also, it's much easier to work with fresh bamboo so that's why we worked this way, to process immediately after harvest.

The ends we weren't using were cut away, though it seemed a little bit of a waste. I did grab one little stumpy piece as well to be able to show a shorn node.

We had six lengths in total to work with but I was so slow that we did not get through a whole lot of this when I was in the studio. All cuts are parallel to the grain, so from the top to the bottom of the plant. First you split in half. Then quarters, eighths, 16ths.

This is all done by hand with a large bamboo knife with a thick back to aid in the splitting.

The skill of course is to make very even cuts so that the pieces aren't wider on one end than another, and that every time you split, you halve the piece in your hand (rather than wavering over to splitting it into 1/3 and 2/3rds, or worse. I wish I could explain this better in words/English but my head is not capable right now).

Somewhere around 16ths and 32nds, you have to pause and remove the inner flesh of the bamboo, which is weaker and burned as trash (or used as disposable chopsticks, I'm guessing). The key here is not to remove it ALL in the first round, because you can take too much away or damage what you want to preserve of the outer grain.

From above, you can see how much inner flesh sits inside the outer layer. Or maybe you can't, but anyhow most of what you see needs to be removed. After you do the first inner flesh removal, you have to split the pieces again into smaller splints because the next removal of inner flesh you want to do on as straight piece as possible. Meaning, all these splints come from a cylinder, so there can be a slight curve if you try to take flesh away from a wider piece. If you keep splitting down, the tiny bits along the circumference of the cylinder are more of a straight line (and now I'm suddenly having math flashbacks as I awkwardly try to explain this thing that makes so much sense if you are sitting there with the plant in your hand).

After this step of removing inner flesh a second time, you just keep splitting the splints into narrower and narrower widths. Every single piece manually! This is absolutely where I would shred everything into toothpicks. My last day was worse than the two days we spent in this studio, where every time I reached a node, the knife would go too far to the edge and I'd lose the length of the splint. Mr. Jo asked if I knew how to ride a bicycle, and said it's like when you go too far to the left and you think to correct that you have to go to the right, but actually the solution is to continue to the left and then straighten out. I didn't tell him that I fell off of a bicycle in a parking lot about 10 years ago, and flew off my bike MANY times in college, so this would explain why knife work doesn't make any more sense than cycling or driving.

I love this trick of using tools to make your life easier: once your splints are thin enough to shave, you have to cut each end to a point or else you can't get the splint through the drawplate. In the old days, you'd cut every single splint by hand to a point (I've seen the two other screen masters in this country do it by hand). Mr. Jo pulls out his grinder and shaves down the splints instead.Even though this requires electricity, I endorse this method!

This was a different batch that we processed, bamboo that had sat around for a while (see how the color shifts from the green quickly to this tan/brown color) in his studio. You can see the points at the end. When working with bamboo that has sat around for a while, you need to get it in water so it's easier to work with.

Now you need to prepare your drawplate. Mr. Jo works a little differently from the other two screen makers. Instead of using extremely rigid steel, he gets softer/thinner stuff that he finds wherever. These four nails are his tools in making the holes. He said that he's always scanning from metal that would be good for this purpose, which explains the bit at bottom right, part of a steamer basket!

You have to take a series of nails that go from dull to sharp to shape the hole and make the right size. It needs to protrude out just so and then you file it, as it's essentially shaving each splint. It's not just a flat hole flush to the surface.

I asked if this was the lid of a rice bowl and he said, it looks like it might be, huh? It certainly does, hammered flat and used for tons of splints.

So much of a working person's tools and studio and waste is like treasure for an artist.

The way that Mr. Jo gets around using such thin and flexible steel for his drawplates is by using a wrench to support it so that it doesn't deform as you pull splints! Brilliant. These are in a vise.

This is the step that transforms these splints that look like a square in cross section into ones that look like a circle in cross section. You have to draw every splint through a drawplate with holes that get smaller and smaller at least two times for regular blinds, probably 3 or 4 times for hanji screens depending on how thin you are able to cut your splints in previous steps.

You can see the shavings coming off of the splint and my weird left hand position that is evading the splint for fear of splinters. You put the point of the splint into the hole on the other side of you, and then pull on the end with pliers and pull through.

See? One man's trash...

So this is what we processed before returning to the dry studio to finish weaving. I had to lay these out on a heated floor to make sure the fresh bamboo was dry before I rolled it all up to take home. You can see where the nodes were in the longer splints. I'll have to cut those all away with pruning shears when I try weaving another screen.On Day 5 (of eight), Mr. Jo had to go to church. I had hoped to have the morning off to sightsee but he insisted I go back to the dry studio and start weaving on my own until he arrived at 2pm. I managed to finish the first half of the screen but had to wait for him to get the edgesticks on. We used two instead of one only because he didn't have wide enough bamboo. Here I'm holding the ends of the fishing line after tying off each one before trimming.

Mr. Jo is inspecting an actual hanji screen to figure out how we're going to set up the lines for the second half of the screen, which have to fall in between the current chain lines on the first half.

If you don't know what to look for you might not see it, but there is ONE line set up closer to the right side of this picture. Instead of taking a needle to thread the line we just used the line itself to get set up on two splints before winding onto a warp weight.

We had only wound the warp weights on one side so that the other half's end was free to thread onto the screen. I think we only got this far before it was time to head to the presentation by the other national treasure. Then we rushed off to dinner with church friends. Just the day before, Mr. Jo had been feeding me candy and I was telling him that I shouldn't eat it because I didn't want to go to the dentist. After we ate a giant meal of nothing particularly hard, I did a sweep of my mouth with my teeth and noticed a large chunk was missing from a back molar. I had probably eaten that piece of my tooth during dinner and called over to my teacher to tell him what happened. Miraculously, my tooth didn't hurt, but I was terrified about what might happen if we didn't deal with it. But after tea, he took us back to the studio to finish threading all of the rest of the lines and winding on warp weights. We worked past 9pm and the guest house owner was so worried that I wasn't home that she texted me!

The next day was Sunday, so we couldn't go to the dentist, and Mr. Jo works on Sundays like it's a weekday, so I didn't get a break either. He took me to the dry studio and told me to start weaving while he went to the other studio to process bamboo. He was back for lunch, and then went back to the studio in the afternoon, then back to pick me up to go home. You know what he was doing? Processing the rest of the bamboo that I was so bad at doing so that I'd have more splints to take home.

He said on Monday we'd go first thing to his dentist, whose wife had taken classes with him a few times and made three screens. He called in a favor to fit us in right before other people arrived, and the dentist was one of those loud proud men who quickly said that all my other teeth were a disaster. My teacher pushed him to get a crown made by the next day because I was leaving on Wed, and they gave me a discount on all the work because of Mr. Jo. I was shocked by how inexpensive a gold crown was, well under 50% of the cost of the same work back home. He stayed with me the whole time on both days and while I felt extremely vulnerable and exposed, I was touched by his insistence on staying and by his small gestures, like taking the slippers off of my feet while in the chair (here, you take off your street shoes at the entrance and swap them for slippers) or holding my face while I was in the chair recovering, asking how my other teeth were. He's only about 3 years younger than my dad and though our interaction could be awkward at times, I could tell he was very concerned.

More than one man has touched me here and aside from the one bad situation, it is clear immediately when the intention is one of care. In any student-teacher relationship, there are degrees of intimacy, and I was surprised by some of it as it felt so deeply feel like fatherly care—and I haven't been able to see my father for well over a year because of pandemic. I felt so fortunate to have met this teacher at this point. By the time that Yi Sunhee took these pictures of me (Mr. Jo was back at the bamboo studio working), I had seen the dentist and had something temporary on my tooth. The friends who have seen these pics already all said the same thing: "You look so happy!" All I felt was utter exhaustion, but it was affirming to have people who knew me recognize that I was finally deep in the stuff that holds so much meaning for me.

By Monday afternoon, I knew I had made decent progress but didn't think I was done given my previous estimate of weaving 2cm an hour. But just for kicks, I decided to measure the second half of the screen to check. It turns out I was spot on DONE! I called Mr. Jo and he said to add the edgesticks and tie off, then wait for him as he finished up in the bamboo studio.

After he inspected my work, we cut the warp weights off for the last time and started to measure off the sides to trim flush. Because the first half of the screen was where I started learning, it was all warped, but Mr. Jo did his best to measure straight.

It's always so satisfying to clean up the ends. I would have trimmed even more but this is one of many instances where you let the teacher do his thing. Maybe it would have been easier if I knew nothing, but in a way, now that I've been teaching for so long, I could feel his point of view better. As we neared the end, which felt like it happened all of sudden, he started to rummage around both studios to find things to give to me. I know this urge very well: when I have dedicated students or ones that I have gotten very fond of (they usually one and the same), I want to give them everything. I start to feel I haven't taught them enough, and so I give whatever I have left. It's part of preparing to say goodbye....for now.One of the details that would have been meaningless to me before I actually made a screen is this one (again, invisible if you don't know what you're looking for): Mr. Jo said that in the future when I weave, I need at every 25 splints or so combine two splints in one half twist to counteract the tendency for the screen to stretch at the ends. You'll see that twice in this picture.

He also showed me how to stretch the screen under weights when I get home to try and get the whole thing flat. Then he rolled it up tight and packed it with all of my splints in a few fastidious packages. We fought about him wanting to give me a bag to take it home in but I insisted that what I had would be fine. This was our penultimate day; I probably could have left after this but as I had a ride home two days later and also had major dental work scheduled, our last day was spent processing the remaining bamboo and learning briefly how to make patterns and work on a much larger screen while standing.

This was one of many wonderful scenes that opened up for me. When we were leaving, the woman who lived next door to the studio that houses other national treasures and intangible property holders insisted that she select some greens for Mr. Jo to take home. We walked into the side of her house and then up stairs that led to a tiny garden wedged between buildings. It was incredible to see what she was growing on that tiny patch of land that you would never even imagine was there from the street. She asked if I was his daughter, who is a year older than me and training in earnest to take on the family tradition. I'm not, but my father would have been glad to know that I was in good hands the entire time.

1 comment:

These are such wonderful records of your amazing days Aimee. By documenting your work with these “national treasures” it’s clear that you are becoming one too - a font of such important knowledge and experience.

Post a Comment