This venue was created by the current national ICPH of gat brim making, Jang Soon-ja. She is 82 and still working but given my time constraints and the late notice, I met instead with her middle daughter of three, Yang Geum-mi. I tried at first to rely on the old Korean ways of finding folks: through people who already know them or other national ICPH making calls. Then when those avenues failed, I went the American way as advised by a younger bearer: call the cultural heritage administration and have them make the calls. It worked! Even when I was embarrassed to make calls from a beachfront cafe that was blasting pop music. Somehow Ms. Yang agreed to meet me and show me what I wanted to see.

Her mother is the national ICPH and her maternal grandmother was as well, though gat making is so complex that there are actually four ICPH because one makes brims, one makes the crown, and two work on assembly. The key being that while the crown is woven of horsehair, the brims are woven from bamboo processed as fine as threads. And I'm not talking about the "bamboo fabric" BS that people fall for, this is actually straight up bamboo that is spliced into threads. Way finer than what I was learning for screen weaving.

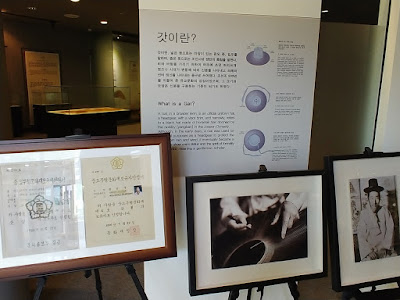

These are images of Mrs. Jang, who still works both in the field, farming, and making gat brims. The reason that I thought the entire hat was woven of horsehair is because people talk about gat being made of that material, and the hats are black. Well, that's because the bamboo is dyed and these hats are coated with otchil, traditional black lacquer from the sap of lacquer trees. But the reason that the brim requires bamboo is that it is so light—much lighter than horsehair, which is heavier or as heavy as human hair. The brims have a very particular flat, almost springy shape, which animal hair could never do. It would hang down and be too heavy.

I love this old image from a tomb, of a person wearing a hat while hunting on horseback, showing that they were in use during the Three Kingdoms period (I think this sign is talking about the period that began just BCE into the first seven centuries or so of the common era).

Let's forget the fact that I didn't realize the exhibition hall would be open (after a two-hour commute on two different local buses, as I was warned this place doesn't have regular hours). If I had known, I wouldn't have taken the longest lunch break ever to sit and relax in a nearby cafe. So I really zipped through this place but was so impressed by all the detail and the fact that it had so many English translations (not completely bilingual but would be fine for someone who couldn't read Korean).

The only distraction aside from the usual being too dark and the glass cases needing to be cleaned (I think from the insides), was all the silica gel packets to help absorb moisture. But given the fact that Mrs. Jang created this entire place with her own funding, these are tiny, minor quibbles.

I can't even tell you how these hats are put together but for sure it's a ton of work.

Not the best picture but had to throw in the bit where I say, Look, hanji! The hanging "gat house" on the right is the hat box for a gat, made with a bamboo armature and covered with hanji. I've seen these in other Korean and American collections.

Korean museum-type places always have these kinds of dioramas, which I remember finding creepy as a child but now I can appreciate, because it's really hard to show the different tools in action or the steps of making things if you don't have a video on a loop or not a lot of pictures.

I'm not even going to pretend I know all the steps of making these brims. Just notice the little tables they are working at, with a basket bottom and a circular top.

These are not good pics as I was shooting through glass in dark areas but I really appreciated so many of the material steps being laid out and explained, from animal hairs to bamboo being cut down from culm to strips and so on.

By this point, I had maybe a few minutes until I was scheduled to meet Ms. Yang, so I can't explain the lovely colors on this brim. Thank goodness they stopped here, because if it was all dyed/lacquered black, you'd never know the work that went into creating the colored spiral bamboo threads.

My desire to have something similar to this, from bamboo slats (and even the curly waste pieces shaved away), to stripped outer flesh, to threads that get thinner and thinner led to all the running around to find bamboo knives, since it was too much to ask my teacher to provide all the pieces.

I never knew there were white gat! Called baeklip, they are for men to wear for their parents' or royal funerals, as the color for mourning in Korea is white.

I also didn't know there were red gat! Called jurip, they are made to wear with military regalia/uniforms.

Ms. Yang was a breath of fresh air after all my stress of being able to even access this info. She is a year older than me and moved to Jeju Island about six years ago. Her mother convinced her to leave Seoul, where she had been for about 20 years, to take up the family tradition. Here are the bamboo slats before cooking in a caustic solution (in the box) and to the very right in a box you can't see is the inner flesh that can't be used. This is the big difference, aside from the type of bamboo being used (Phyllostachys nigra 'Henon'—whereas the screens and fans and so on use Phyllostachys bambusoides), from other bamboo crafts I've studied and seen. The alkaline solution softens the bamboo and makes it more pliable, which is how you can make threads. Similar to cooking fiber for papermaking, you can't just leave the pot and forget about it, you have to watch it carefully and check on it, AND you can use the discarded parts of the plant as your firewood.

After being born and raised in Jeju like her mother, Ms. Yang studied visual design and worked in Seoul, which she loved as she is a city person. She is seated here with a leather strap tied around her thighs, which protects her leg as she lays a knife against a piece of outer bamboo and pulls it from center to end to shave away more and more of the inner section. Then she turns it around to shave away from center to end on the other side. You have to soak these pieces in water from the prior day, as there's no way for this to work dry.

She ties fabric around her fingers to keep from slicing them with this sharp knife, which she is holding upright against the end of the shaved bamboo slat to make a bunch of tiny tiny cuts. She thought her older sister would take on the tradition, but she couldn't, and then her younger sister couldn't even though she was interested, because she was getting married and now has two kids and lives in Ohio.

After making those cuts, she takes a long stick and pokes it through a hole in the leather strap and places the other end into her abdomen (I see this so much in Korea, using every part of your body as a brace or tool or stopper). That becomes a little platform for her to start easing these cuts apart so that they start running down the length of the slat, which she then has to keep bending back and forth with equal force so that the slivers separate evenly from top to bottom. She had just cut her fingernails so she had a hard time getting the bits started, but explained later that she has since rubbed away her fingerprints on her thumbs. I hear her, as I've had problems getting digitally fingerprinted in both the American and Korean systems (from rubbing them away, twisting and twining hanji). If you watch the video of her mom working, there are some differences, like how she twists her strap into a figure eight to place around her knees, and how she works on top of her knife rather than a piece of bamboo (start at about 11:45 to see but the whole thing is worth watching even if you don't know Korean - you can just skip the talking heads parts and how it weirdly starts in Russia).

All these weights are necessary when weaving these brims because the bamboo is so light that otherwise it would lift up. There are four thicknesses of bamboo thread necessary to do this and they move in succession as you go from the center to the outer parts of the brim. The long pieces that are tied in the center with a little white thread are actually bamboo that are split slightly thicker to act as needles for weaving. You stick the bamboo thread into the back of the bamboo needle.

Ms. Yang showed me the different thicknesses of thread and also said that the best paper to wrap these in are Korean calendar pages.

We talked a LOT about knives. These two she ordered from the national ICPH in Gwangyang (south Jeolla province) who specializes in sword making (Jangdojang). I was surprised by how light they were but she said while one is good, the other is still not quite right: too light, and not a wide enough blade. She said she has ordered over 100 knives since she began this work and still has not gotten the perfect knife. Her mom uses the one she inherited from her grandmother. We talked about sharpening, as I saw a stone right there and she does that often as it makes her work easier. I mentioned that the older bamboo folks I've met don't seem to sharpen a lot and she said her mom doesn't either, so maybe she just doesn't have the skill yet. Also, sharpening a lot means you need to replace your knives more often. She very kindly traced and measured the knives for me and asked if I find a good smith, to alert her! If only.

Remember those little work tables? It's a basket that is the same on top and bottom, there's just a middle platform that holds your tools and whatever else you'd need. The middle is creased like that to accommodate your knees as you sit at it. Brilliant.

Of course, just as there are barely any good smiths left because there's no way to make a living, no one makes these baskets anymore to serve as weaving stands. This is the bottom of the basket, though if you turned it upside down it would be the top.

Such a great workspace, you'd never know what was inside! Overall, it was wonderful to hang out with Ms. Yang. She said this was not her fate, but that maybe it was: she never wanted to be the one to bear this tradition; she thought that her one of her sisters would do it. She tried to run away but it didn't work, and here she is. So she tries to work with ease, and since she can't make any money doing this because ZERO Korean people buy gat anymore, her income comes from farming Hallabong: delicious citrus fruit that her father also raised. He is 95 and she grew up doing errands and so on, so just like the tradition she is learning from her mom, all of this work comes to her easily. It's hard but fun, and she said it's a good balance. I've heard that before from lots of people: when you do fine, detailed work, you have to balance it with really physical, outdoor stuff.

Because I didn't want to miss the concert that evening, I rushed out and RAN across the street to make it to the bus stop again. The phone apps these days tell you exactly how far the bus is, and because I have no sense of time, I ran. I probably didn't have to run but that's me, always have to arrive early. I'd rather wait a few minutes than be running right alongside the bus. This is the cafe that happened to have opened recently that was on the corner of the road where the exhibition hall was, so this is where I had lunch before our meeting. I found the shiny ceilings interesting.

The heart was too sweet but the lemongrass tea was lovely and the duck sandwich just right. I had arrived maybe an hour and a half early (see what I mean? So much being on time anxiety) so I lingered long enough to hear that they must have had some playlist of all American black female hip hop on rotation, though in general all over Korea, you hear US hip hop. Because I hadn't had much time to myself until then, I wrote a bit about memories I had forgotten to share, like how I carried around a giant head of cabbage for two weeks through three cities because I had ordered it not thinking I was going to have to travel so soon. I ate raw cabbage for 17 days straight, even after my tooth broke and I had to start the dental work.

Also, this week my local media outlet back home put out a story on how to support Asian American women visual artists, for which I gave a late-night exhausted interview because of the time difference. I was glad they interviewed one of my past students, Chi Wong, though I also hope this is not just an AAPI month/aftermath of visible violence tokenism.

Finally, I really enjoyed Gary Friedman's post about why he takes pictures (to tell stories), as well as his ideas behind teaching: "There’s nothing so complex that it can’t be explained with proper care – even if you have to take your time and explain things in layers."

The next layer of this Jeju story will take us back to the sea!

No comments:

Post a Comment