God bless this man, in the most non-denominational, non-religious way possible. As with many of my past searches, getting to him was not a straightforward or easy path, but I am grateful beyond words that Jo Dae-yong accepted me as a student. He is the national treasure of making bamboo blinds, or more accurately the national intangible cultural property holder of property number 114, designated in 2001. Of the three holders in the country, he is the only one appointed at the national (rather than regional/provincial) level, and takes this responsibility very seriously.

Because I'm still a novice to this practice, I didn't notice until my last day that of course this window to the street had one of his incredible screens hanging in front of it.

These are incredibly subtle pieces of art that used to be a big part of Korean culture but have disappeared. Mr. Jo is pointing out the patterns that he makes and had already told me during my initial visit (when I asked to be taught) that there was a government factory in the Joseon era that employed people to make these screens but they kept running away, being captured and brought back to make more. After learning the process, I do not blame any of those people for trying to escape. This is an incredibly tedious practice.

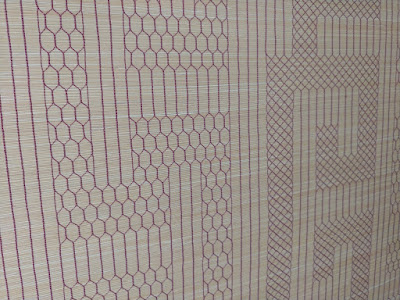

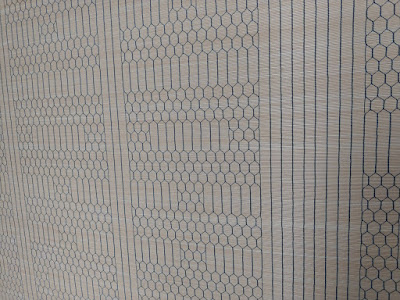

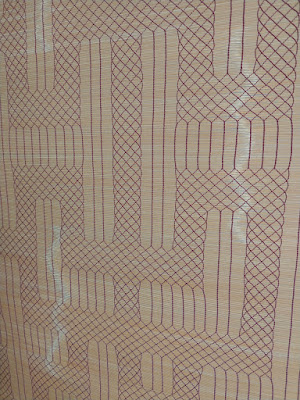

My pictures really do no justice but here are some close-ups of the patterns.

You'd think you would only need a certain number of threads or warp weights to start but it's usually double what the normal person would imagine, because at some point, you have to split the lines. That means you start with doubled-up threads that travel together to create a straight line, then split to start creating the hexagonal patterns. LOTS of math and prior planning/drawing!!

The other thing that is not totally evident is the splint size of the bamboo, a millimeter or less. Though other bamboo crafts might require a smaller splint size (say, the size of a hair), this is less than a millimeter times thousands of splints. Which are all hand processed! I'll show that in the next post but for now, just know that this is an insane amount of work.

The short screen was traditionally used for windows of sedan chairs (palanquins, known in Korean as gama). My gama story that I tell over and over is about hanji chamber pots but I never thought about all of the other accoutrements necessary in gama culture. Just as a house doesn't just require windows and doors (like when I learned how Korean architecture led to narrow art to fit in the skinny spaces above and beside sliding doors), a gama is bordered on most sides with a woven bamboo screen.

These are also giant screens if you think about how they are made, one splint at a time. In this one, you can see more clearly the zigzag pattern of the bamboo nodes. From the moment you split entire bamboo, you have to keep each pole organized as you splice from 2 to 4 to 8 to 16 to 32 and so on. Each discrete zigzag is one node, so you can see the length of each bamboo stem. I'm slow with numbers in translation so I can't tell you exactly how many small splints you get from one tubular section of bamboo but it's definitely well over 100. Of course you also have to keep these in order while weaving as well.

Close up of the nodes, which are almost like shiny scars of the most exquisite kind.

This is a screen Mr. Jo decorated with ink rather than a sewing pattern. But this required a lot of tests, to figure out how diluted the ink needed to be and how thick, so that it wouldn't go all over the place.

The key is that you shouldn't be able to see the ink bleed through to the back of the screen.

When I said that Mr. Jo takes his responsibility seriously, that includes tons of research. He grew up not being a particularly studious kid, but as the youngest of eight, he actually enjoyed hanging out with his father, who made screens when not working as a public servant. He didn't have as many years of education as people who demand automatic respect, but has spent more years studying screens and screen culture than most people I know spend in formal education. On a trip to a royal palace in Seoul, he noticed the wooden tools used to raise and lower screens in the doorways. The screens themselves were long gone, but he inspected the spools and had them replicated from wood and metal.

These are larger splints and with these, you can buy them from Damyang, the location of the big bamboo market in Korea, where a machine will pull long splints for you. Then he has them lacquered with colored or plain lacquer, or he does some dyeing himself. He always matches the thread and edging cloth colors, and always orders threads dyed with specific colors. This can take a while as silk threads are less and less common. This particular pattern was inspired by something he saw on TV, so he pulls his ideas from both contemporary and historical visuals.

My photos are not great but I love the little folding screen.

This is where he works standing up on giant screens. Those nuts and bolts are wrapped in aluminum foil before wound with silk threads and they are HEAVY. I only know because he made me weave a bit with him on my last day. At least he can watch/listen to the TV while working. I'm not good enough yet to be able to look away for long.

I was doing this one handed with a tape measure that wouldn't stay open so I don't have it positioned well but wanted to indicate how much finer these grooves were in terms of distance than what I was doing.

My screen in progress.

Once Mr. Jo agreed to teach me, I was told by the intermediary to pack my bags to travel to Tongyeong on a certain day. We arrived to see him at 5pm and only then did we sort out details of my logistics, like where I'd sleep. After searching on our respective phones, Mr. Jo found a guest house that only accepted women that happened to be across the street from his apartment complex. I stayed at Good Day and was incredibly well cared for by the woman in charge, who worked with her husband downstairs on their interior design business (which explained why all of the doors were so fancy and the inside of the guest house so nicely done).

Across the street didn't mean that the drive was easy; there are his apts and a busy main drag that leads to the main/older part of the city. He was living in the newer area on land that was created along the coast, so we were inhabiting what used to be water. Every morning, he'd pick me up and every evening, he'd drive me home. Aside from his frightening habit of running red lights (I truly thought I was going to have my legs shattered by a truck and had to confirm with other Koreans that a red light means the same thing here as back home), I felt very safe the whole time.

He mapped out a schedule that we guessed would take a week. It was a little more, so that from the first morning, I spent 8 days under his tutelage. The first thing we did when he picked me up was stop at a fishing store to find line fine enough to make a hanji screen. The guy at the store didn't want us to buy the appropriate size because it was expensive so we went one half size up, and guessed with 5 spools. We only needed 4 but this was a new adventure for both of us: he has never made a hanji screen and I've never had such an attentive teacher. The first job once we got to his clean studio was to tie two lines to a nail, and then stretch it across to another nail.

That one was on a clothing rack weighted by tons of warp weights (you can see the stacked containers in front of his feet). He stuck the two spools of fishing line on a piece of bamboo root and walked back and forth to measure out the line and tie it off. You need enough line that you can have some extra on each warp weight to keep the line from flying away, different from what the hanji screen maker's wife showed me: they have lead threads already tied onto each warp weight so you can use the entire length of the line.

I had to pick out the heaviest weights, which are covered in hanji (replaced when the paper falls off), which are still only about half the weight of what the hanji screen maker uses. But that's fine, we were doing the best we could and I didn't expect at all to be able to use this screen to make paper. It's the first one: practice! The one where you make all the mistakes.

These are holding down the ends of the fishing line.

And this table has the middle of the line closest to Mr. Jo. He will take one half of each line, wind it onto the warp weight, and then locks it on about 20cm from the center of the line.

Then he uses his foot to keep the wound thread taut and still while he pulls out the other end of the line to wind around another warp weight. This took a while for me to get but he was so fast, even though the line was so much more slippery and invisible than the silk threads he usually uses.

After hanging all of the weights onto the weaving frame and making sure they are all at the same hanging length, he started with one splint. He was about to start in the traditional way of making hanging blinds but when I showed him how hanji screens worked, he saw that we had to start in the middle and work to the end. This was a careful balancing act the entire time I studied with him, because he knew so much more about screens and bamboo than I did but I knew so much more about hanji and hanji screen use than he did. So there were times I would point out things and other times that I just let it go and obeyed orders to maintain what seemed like the appropriate deference.

Mr. Jo has more splints in his hands. The part that I didn't document well is that we started weaving the first two days in the clean studio with splints he had already prepared for previous projects, leftovers, and so on. So though they were fine, they were not all the same size as they were from different batches, and they still had nodes intact—since that is how he works. My job at one point was to cut out all the nodes, which he took over doing when I was weaving. Then we had to bundle the cut splints and rubber band them so that each time we started a new row or had to complete a row, we checked against the bundle to choose the splint closest in length to finish the row without excess at the end. That's not exactly how hanji screens are made but that's okay, this was part of the practice.

I can't remember if this is when he let me take over or if this is after I took over to start practicing. On the finished screen, it is SO obvious where I started! As a teacher, I realized Mr. Jo had chosen the right order of learning, because while this felt impossible for two days and I was in a lot of pain from sitting on the floor, looking down, it was nothing in comparison to bamboo harvesting and processing.

By the end of Day 2, I needed to stretch my legs. We got to about 27 cm, which seemed amazing considering that we achieved 10cm on the first day (it's easy to forget the time spent getting materials and setting up the frame). I almost forgot to explain, since each thread has a weight on each end, you go down the line and take the weights in opposite hands and cross them to make a half twist. Don't ask how many times I got threads tangled or how many times threads wound off the weights and so on.

This was Day 5, when I was told to go myself to the studio and work to finish the second half of the screen (5-6cm left), which I did faster than I feared (I had timed myself at about 2cm/hour but eventually got faster). By now, I was so happy that I didn't have to process bamboo that I wore nicer clothes since we went later that afternoon to another event. Thank goodness I did, since I was unexpectedly introduced to the audience. This entire time in Tongyeong was over the top intense but also deeply fulfilling in a way that nothing else here has been on this particular trip. I had heard so many no's but it's true that all you need is one yes, even after countless rejections. Thanks to Mr. Jo for giving me a chance (and that pink bracelet that he had made using maedeup, traditional Korean knotting)!

No comments:

Post a Comment